Animal fibers have a long, long textile history. Animal fibers all share some similar traits – no matter whether the animal is a sheep, a camel, or even a rabbit. But each animal also has some unique trails that make its fibers stand out from other animal fibers.

In this article, we’ll look at the basic facts you need to know before you start knitting with animal fiber yarns. They are great insulators and perfect for cold weather but animal fibers do have some drawbacks that need to be taken into consideration before you start knitting with them.

In this article, we’ll take a look at some of the advantages of knitting with animal fibers as well as their disadvantages (and when you’d want to avoid using them). We’ll also discuss:

- Turning Animal Fibers into Yarn

- Basic Properties of Animal Fibers

- Caring for Hand Knits

- A Closer Look at Different Animal Fibers

Let’s take a closer look at the many animal fiber yarns that can be used for knitting – a bit of history, their properties, how they are to knit with, when you’d want to use them and when you’d want to avoid them.

Some links below are affiliate links. If you click through and make a purchase I may receive a small commission at no extra cost to you. See the disclosure policy for more information.

Turning Animal Fibers into Yarn

The many different fibers used for knitting can be divided into four broad categories – animal fibers (like wool, silk, and alpaca), plant fibers (like cotton and linen), biosynthetic fibers (like rayon and bamboo), and synthetic fibers (like acrylic and nylon).

Animal fibers can be the fleece of sheep or other specialty wools like cashmere, mohair, and alpaca (and plenty of other animals), fur from Angora rabbits or brushtail possums, and even silk from the cocoons of silkworms. If the fiber comes from an animal – it fits within this category.

The fibers are collected from the animals in various ways. Sheep and many other animals are sheared, Angora rabbits are combed, the cocoons of silkworms are collected and boiled to soften the cocoons and unwind the silk filaments.

Once the fibers are collected, there are a few processes that can be used. First they are scoured, or washed, to remove debris. Then, each yarn can go through a different process. Some are carded and woolen spun. Others might be carded, combed, and then worsted spun.

Carding & Combing

The first process that animal fibers go through to become yarn are the carding and combing process. The first step, carding, is the process that’s used to smooth out the fibers. This can be done by hand with carding paddles that look like large brushes. The fibers are placed on one paddle and the second paddle is placed on top before pulling the paddles in two different directions. This process blends the fibers together and removes any residual foreign matter. In a mill, the process is done on large machinery.

After carding, the shorter staple lengths are bundled with other carded lengths and twisted to create a ‘roving’ while the longer staple length fibers are combed (with no twist).

Silk is the only animal fiber that doesn’t go through this process because it’s already in a long, thread-like filament when it’s unwound from the cocoon. Instead, three or four of the filaments are twisted together.

Spinning

Once the fibers have been carded and combed, they are ready for spinning. The basic process involves drawing out the fibers and twisting them together using a spinning wheel or a drop-spindle. Depending on how many fibers are drawn out and how tightly or loosely they are twisted affects the final outcome of the yarn.

A woolen-spun yarn, often used for short staple fibers, draws out a larger amount of fiber while spinning and results in a plush, soft yarn with a fuzzy appearance. These yarns are softer, weaker, and more likely to pill (but they are wonderful for colorwork garments because the soft yarn ‘blooms’ and fills in the gaps between colors).

The worsted-spun yarn is used for the longer staple fibers and is spun so more twist moves into the fiber. These yarns are smoother, stronger, and have more elasticity than woolen-spun yarns. They are also less likely to pill.

Both of these create a strand that is referred to as a ‘single’ or a ‘ply.’

Z-Twist & S-Twist

During the spinning process, the fibers can be twisted to the right or to the left. Fibers that are twisted to the left during spinning are referred to as ‘Z-twist’ while the fibers that are twisted to the right are referred to as ‘S-twist.’

Plied Yarns

After the fibers are spun, they can then be plied. Two or more singles are twisted together to form the plied yarn. If the fibers were initially spun with a ‘Z-twist’ they will be plied together using an ‘S-twist’ (or vice versa). Most commercially-available yarn uses ‘Z-twist’ singles plied together using an ‘S-twist.’

The plying process can vary from one yarn to the next – one might not be plied at all and remain a single, two or three might be plied together, or even two plied singles might then be plied together with another pair of plied singles.

This whole process, from combing to plying, varies from one yarn to the next and can produce highly individual yarns – even if they both come from the same animal fiber source.

Properties of Animal Fibers

Now that you know how all these animal fibers can be turned into useable yarn, let’s look at the properties that are inherent in animal fibers. While each animal has specific properties that define its individual fibers, animal fibers share some basic general characteristics.

The first general property that animal fibers share is their warmth. Fleece and furs are basically hair, and like human hair, they have different layers. The outside layer, the cuticle, is covered in scales. Sheep, for example, have scales ranging in number from 600-3,000, depending on the breed. The scales along the shaft of the fiber allow heat to pass through to the next layer, the cortex. The cortex traps this heat and creates a warm, insulating barrier.

These scales also cause the fibers to felt, if they are introduced to heat, moisture, and agitation. The more scales a fiber has, the coarser the wool, and the more likely it is to felt. The finer the wool (because it has fewer scales) the likelihood of felting is reduced. For example, most (not all) sheep’s wool will felt, while other animal fibers, like mohair and cashmere, are smooth and fine, and less likely to felt.

Animal fibers are also lightweight, elastic, and generally receptive to dye. Of course, these characteristics vary from one animal fiber to the next.

Caring for Hand Knits

All of these animal fibers need the same care needs – they are hand washable (but always check the yarn label for specific care instructions for your yarn).

Hand washing: Fill a small basin with cool to lukewarm water and a little mild detergent. You can include a small amount of hair condition if the fiber is particularly scratchy. Submerge the garment in the liquid, pressing the garment down into the water without agitating it. Let the garment soak for a few minutes (up to 30 minutes or more for hardier fibers like sheep’s wool, less time for delicate fibers like silk or cashmere).

To rinse the garment, hold it to one side of the basin as you drain the water and add fresh water. When you’re ready to dry the garment, gather the whole garment in your hands, lifting it gently from the water and carefully squeezing out the water. Place the garment on a towel, roll it up, and press out the excess water.

Wet-blocking: After washing, place the garment on a dry towel or mesh sweater dryer and place it in its final shape, being careful to lightly stretch any lace or other openwork designs to showcase them. If needed, use pins or blocking wires to further block the garment to its final shape and measurements.

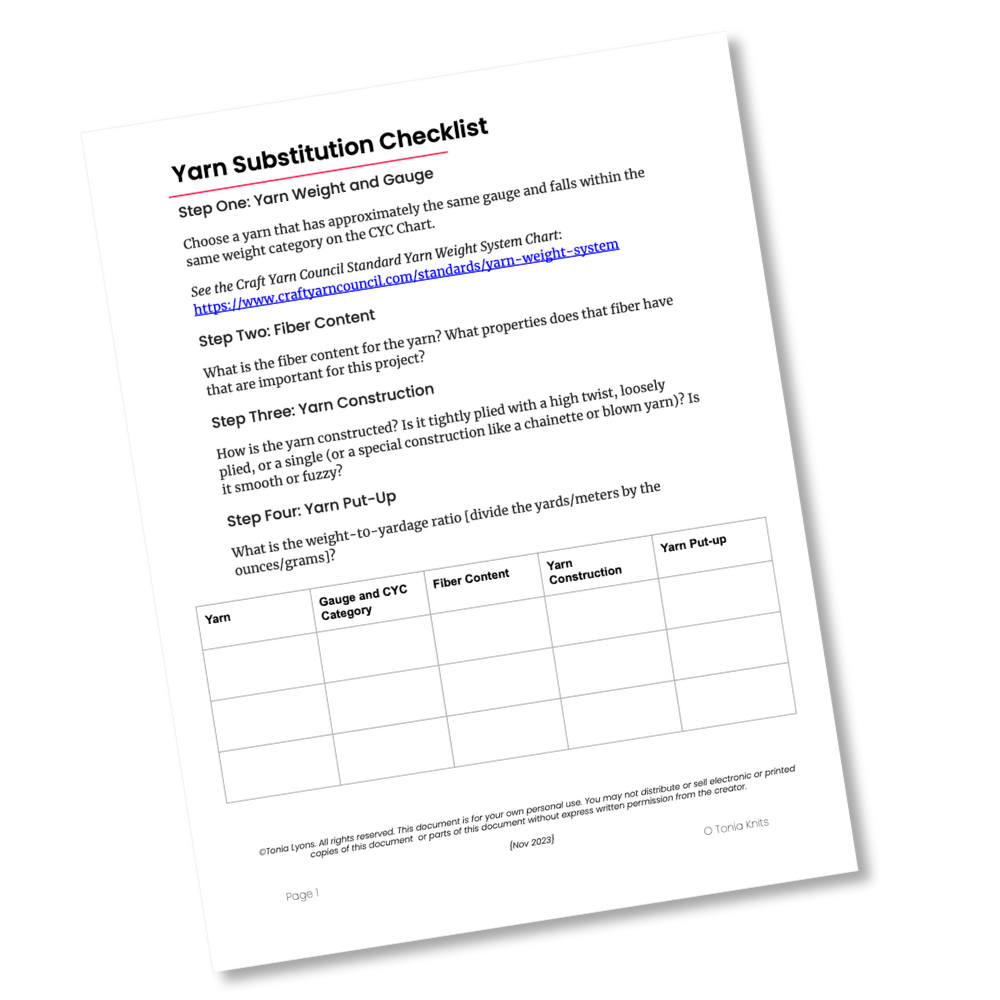

Get the Yarn Substitution Checklist

Fill in the form below to get a free copy of the Four Step Checklist for substituting yarn. Use it for your next knitting project!

A Closer Look at Different Animal Fibers

While sheep’s wool is the most popular and most used animal fiber, there are plenty of others you may want to try. If you want to learn more about knitting with a particular animal fiber, this section covers the animal fibers you’ll often find in commercially-available yarns and yarn blends.

Knitting Wool Yarn

Sheep’s wool is one of the most popular animal fibers for knitting (actually, it’s probably the most popular fiber for knitting – outside of acrylic). It’s versatile, warm, and makes a great choice for so many projects – from soft Merino used for cowls or garments and accessories that will be close to the skin to lofty, scratchy Icelandic wool that makes beautiful (and warm) colorwork sweaters.

Wool is wonderful for so many different reasons but at the top of the list is the inherent memory and elasticity that wool fibers have. This combination makes them truly versatile. You can make garments that will stretch and move and still hold their shape – ribbing, cables, and a wide variety of garments are all beautiful when worked in wool yarn.

Learn more about knitting wool yarn (covering basic information, properties of wool, advantages & disadvantages, pattern choices, and how to properly care for your wool garments).

While wool is a wonderful fiber for knitting, many people dislike the need to hand wash their knits. If that’s the case, take a look at the next section – superwash wool.

Knitting Superwash Wool

Superwash wool uses a chemical process to remove the scales from the wool (the original method burned off the scales using a chlorination process). Instead of removing the scales, newer methods coat the wool fibers in a plastic or polymer resin that glues the scales down. When these scales are removed or glued down, the resulting yarns are smooth and the wool fibers won’t felt together (like natural wool has a tendency to do).

For those who dislike the handwashing that natural wool garments need, a ball of superwash wool may be a good choice. But superwash wool has its own drawbacks and things that knitters need to be aware of before knitting garments. At the top of the list is the tendency of superwash yarn to stretch and grow over time. This happens because the naturally sticky wool fibers have been coated with a polymer or removed so they can no longer stick together. There are some things to mitigate the instinct of superwash wool to grow, but it’s certainly something knitters should know if they plan to knit with kind of yarn.

Learn more about knitting superwash wool in this article (learn more about the process of creating superwash wool, its properties, advantages and disadvantages, what you need to know about knitting with it, and how to care for your finished garment).

Knitting with Silk Yarn

Silk yarn and yarn blends are wonderful to knit with as the silk adds a smoothness and softness to the knitting experience. It’s also very strong but does weaken when wet and is prone to fading. It works best when it’s blended with other fibers (especially wool). And a little goes a long way – the addition of 5 or 10% silk to a blend adds all of the benefits of this beautiful fiber. But because it is prone to fading and can get heavy, it’s best to stick to blends where silk is limited to about 15% of the fiber contents of a particular yarn (particularly for sweaters and cardigans).

Silk yarns are a wonderful choice for all types of garments – shawls, sweaters, cardigans, cowls, hats, and other accessories. It adds wonderful sheen, strength, and drape to hand knit garments. But it must be treated gently when it’s wet, so be sure to handle it with care.

Learn all about knitting with silk yarn – its advantages and disadvantages, choosing appropriate patterns, how the silk is collected and turned into yarn, and how to care for your finished garments.

Knitting Cashmere Yarn

Cashmere comes from the Kashmir goat, which is native to the Himalayas (but can now be found in various places). It has two coats – the coarse outer coat, called the ‘beard,’ and the finer undercoat. Both of these coats are combed from the goats once a year and the fibers are separated. Each goat produces just a few ounces of the cherished undercoat each year – which is why this fiber is so expensive.

The collected fibers are very short and very fine so, while they feel silky and smooth, they are difficult to spin into a yarn that will wear well with time. It’s often blended with other fibers that are easier to spin into a useable yarn.

Because it’s an expensive fiber, it’s best used in a blend with other fiber types – a wool and cashmere blend is a great choice for a sweater. But 100% cashmere yarns can still be used for smaller accessories that won’t get much wear and tear (cashmere can be weak and prone to pilling). Things like cowls and hats can be beautiful when knit with 100% cashmere.

Learn more about knitting cashmere yarn – understand its properties, how to properly care for your cashmere garments, and how to choose appropriate knitting patterns.

Knitting Mohair Yarn

Mohair comes from the fleece of the Angora goat. The goats are sheared twice a year and, interestingly, they produce a single coat of fine wool (most wool-producing animals have double coats). The fleece that’s commonly used in knitting comes from the Angora kids (young goats) and the fiber is known as kid mohair, which is the softest and finest grade of mohair. This also makes the mohair used for knitting an expensive fiber – because it only comes from young goats.

Another interesting fact about mohair is that the cortex (the middle of the hair shaft) contains air pockets. This makes the fibers very lightweight as well as making them very good insulators – so mohair is a great choice for garments that will keep you warm in cold weather. It’s commonly brushed and blended with silk to create a lace weight mohair blend that’s often held double with another thicker yarn to provide additional warmth and a beautiful halo to the finished garment.

Learn more about knitting mohair yarn – all about the advantages, disadvantages, important things to know before you knit, and how to properly care for any projects that include mohair.

Knitting with Alpaca & other Camelid Fibers

Camels (both dromedary and bactrian), alpacas, llamas, vicuñas, and guanacos are all part of the camelid family and the fibers collected from these animals share some similarities. The fibers are hollow which makes them lightweight and retain heat (making them quite warm).

The fibers in the camelid family are also soft, have beautiful drape, and are even water resistant. They are also lanolin-free which makes them a good choice for people with sensitive skin or those who are sensitive to the lanolin in wool. They can be used individually but projects knit with these fibers will droop and sag with time because the fibers have no memory and little elasticity.

For this reason (as well as the fact that they are less common fibers and more expensive) you’ll often find them blended with other fibers. Alpaca is commonly blended with wool to improve the memory of the yarn so projects will hold their shape. It’s also combined with silk blends and these yarns are wonderfully soft with gorgeous drape – they really make great hand knit shawls.

Learn more about camels (both dromedary and bactrian), alpacas, llamas, vicuñas, and guanacos in this article: All About Knitting Alpaca Yarn (and other Camelid fibers)

Knitting with Luxury Yarns

These special, luxury yarns are in a category of their own because they are more difficult to find in commercially-available yarns, they are rare, and they are expensive. While there are others, the most common include Bison, Qiviut, Angora & Possum.

Bison and qiviut share some common traits – the fibers from the soft under coat of the bison and musk ox are both similar to cashmere (if you’ve ever knit with cashmere you know how soft that can be), warmer than wool (qiviut is actually eight times warmer than wool), very durable, and they don’t shrink.

Angora and possum furs also share some similar traits – they are both extremely soft, lightweight, and warmer than wool.

Any of these luxury fibers would be beautiful for small, cherished accessories that won’t see much hard use. A soft cowl or hat would be beautiful in any of these fibers. Because of their tendency to halo (especially angora and possum), choose patterns that don’t require strong stitch definition. You won’t see your intricate stitch patterns as well with these soft, lofty yarns.

Learn more about knitting with luxury yarns – looking at their properties, how the fibers and furs are collected, and how to care for those luxurious finished knitting projects.

Now you’re ready to begin knitting with animal fiber yarns. If you’re looking for more information about different fibers for knitting, take a look at the resources and articles linked below.

More About Yarns & Fibers

- The Knitter’s Book of Yarn by Clara Parkes (available at Amazon)

- Yarn Substitution Made Easy by Carol J. Sulcoski (available at Amazon)

- The Fleece & Fiber Sourcebook by Carol Ekarius & Deborah Robson (available at Amazon)